I’m Bach.

I crack myself up. But anyway, yeah. I’m back with more notes on the aforementioned MOOC, Methods for Solving Problems, hosted on Coursera.

So let’s go.

First reading assignment: “Recognizing, Defining, and Representing Problems” by Pretz, Naples, and Sternberg (Yes, I’m still on the first reading assignment. Let’s not get judgy.)

Notes:

The problem-solving process is described as a cycle (see Bransford & Stein, 1993; Hayes, 1989; Sternberg, 1986)

The problem solver must:

- recognize or identify the problem

- define and represent the problem mentally

- develop a solution strategy

- organize their knowledge about the problem

- allocate mental and physical resources for solving the problem

- monitor progress toward the goal

- evaluate the solution for accuracy (efficacy)

Describing the problem-solving process as cyclical is just that–a description. NOT a prescription.

Do NOT take it to mean that all problem solving proceeds sequentially through ALL these stages in THIS order.

To be successful, you must be FLEXIBLE.

The problem-solving process is described as cyclical because once it is completed and the problem solved, this usually gives rise to a new problem and the process begins again. (The solution to every problem spawns another problem–albeit maybe a more pleasant one the next time around?)

Example: hearkening back to the carpooling scenario from the first post, we have solved the issue of parking, but now what do we do about people’s divergent schedules?

Hence, a solution to one problem gives rise to another.

Problems Can Be Broken Down into 2 Classes

- well-defined problems

- problems whose goals, path to solution, and obstacle to solution are clear, based upon the information given

- these can be easily broken down into a series of smaller problems

- example: how to calculate the price of a sale item

- ill-defined problems

- problems that are characterized by the lack of a clear path to solution

- these often lack a clear problem statement

- this makes problem definition and representation difficult

- example: how to find a life partner

- how do you define “life partner”?

- what traits should that individual have?

- where do you look for a life partner?

- it takes considerable work just to formulate the problem

- even then, the path to solution may remain unclear

- it may require multiple revisions to the problem representation to find a path to the solution

- ill-defined problems can also lead to more than one “correct” solution

- the problem cannot be broken down or easily defined as a set of smaller components

- often requires a radical change in representation

- example: you have a full jug of lemonade and a full jug of iced tea. You simultaneously empty both jugs into one large vat, yet the lemonade remains separate from the iced tea. How could this happen?

- we form a mental image of the drinks being poured

- we must adjust our mental representation

- we might assume that the drinks are liquid, but that is only an assumption

- the drinks are frozen

- we often make unwarranted assumptions in our everyday problem solving, which can interfere with our ability to discover a novel solution to an ordinary problem

Thoughts:

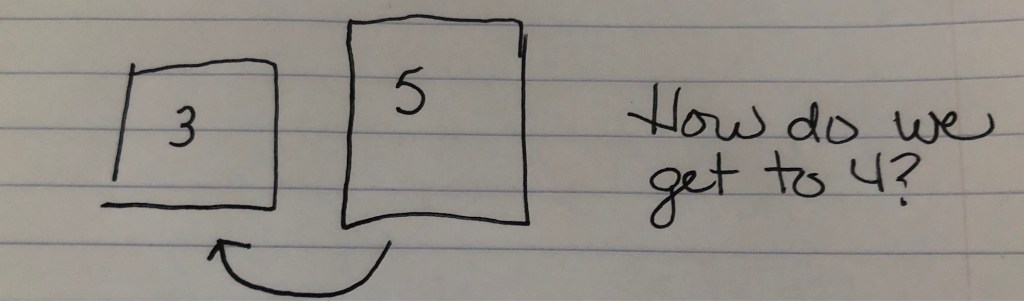

So, did anybody read that last example and NOT think about that scene in the Die Hard movie where Samuel L. Jackson and Bruce Willis have to solve the riddle with the jugs of water at the fountain? Obviously, I did. So, I went looking for a clip of the scene and tried to follow along, but I think the scene cut out or I missed something, because I had no idea how they solved it. Basically, the riddle is this: you’re at a fountain and you have two empty jugs–one with a 3-gallon capacity and one with a 5-gallon capacity–a scale, and a ticking bomb. You need to measure out 4 gallons of water. Once you have precisely 4 gallons of water, you set the jug on the scale. If it weighs the right amount, this will then deactivate the bomb. How do you do it?

I found this website, mindyourdecisions.com, which goes through the riddle and shows you how to solve it. Once the site owner, Presh, walked through it, I felt like an idiot for not getting it.

Realtalk: Once I came back here and started writing about it, I forgot exactly how he solved it so I had to walk through it again myself on paper. Once I did that, I asked myself: where did my process go wrong? Here’s what I got.

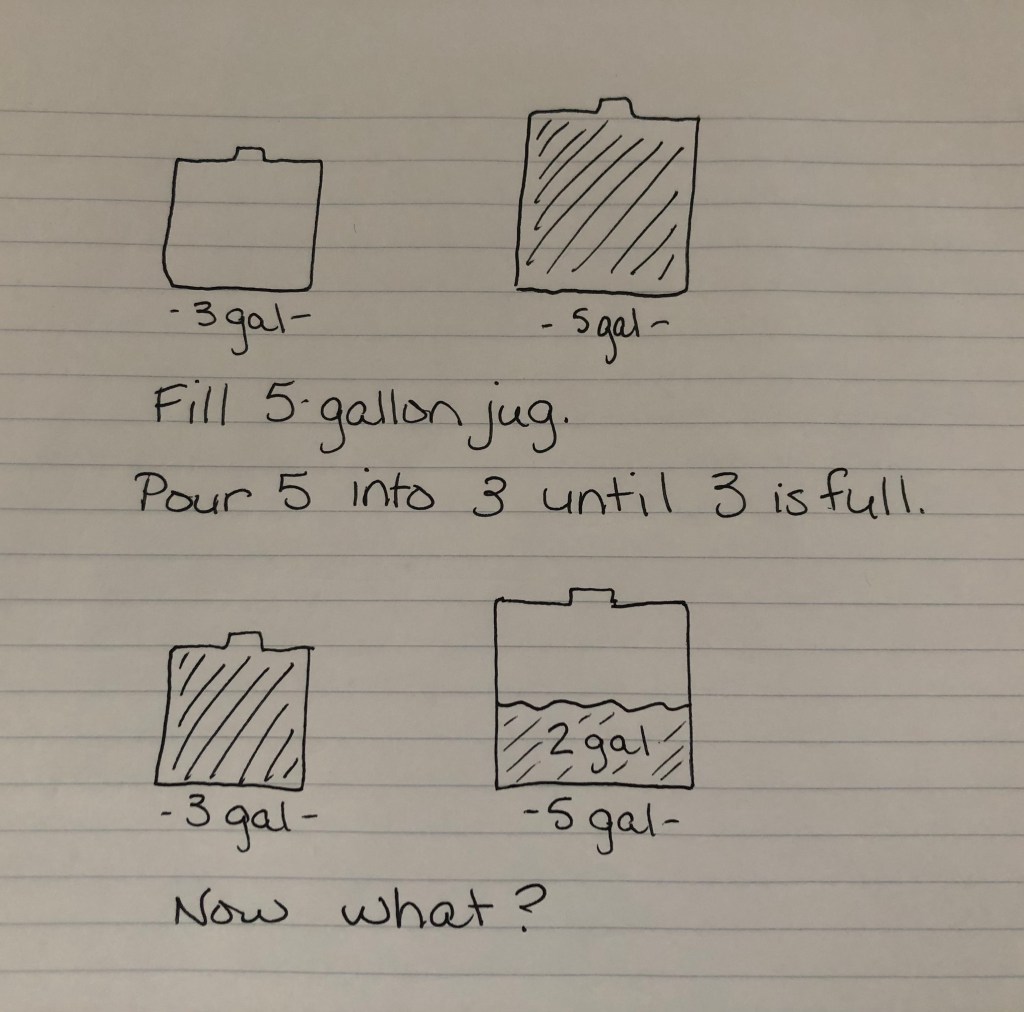

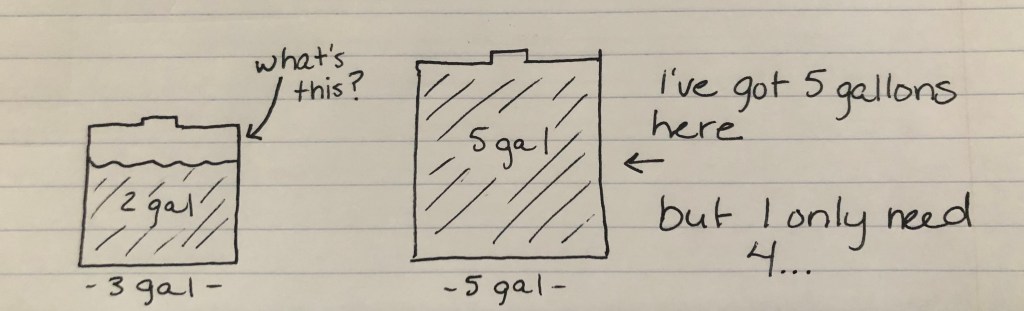

So, I immediately went for a way to visually represent the problem. I’m a visual person. Anyway, we’ve got our 5-gallon jug of water. We start pouring it into the 3-gallon jug; once that one is full, we are left with 2 gallons of water in the 5-gallon jug. So, decent start, right? But where do we go from here? Now I’ve got 5 gallons of water split between two jugs. If I had a third vessel, I could dump the 2 gallons from the 5-gallon jug into the extra container, and then repeat the first process to get another 2 gallons in my 5-gallon jug. Someone get me a garbage bag or something, stat! Nope. That solution strategy is a no-go. Now what?

And here is where I began making assumptions, which truly made an ass out of me. (SIDEBAR: that hyperlink goes to an unexpectedly cool article on unconscious bias. Score!)

What do you think my main assumption was? Do you have an assumption here? What are we taking for granted and/or misconstruing as a given in this equation? MY assumption was that ‘of course I need to keep the same water in the jugs that I’ve been working with this whole time! Dump any of it out? Psh!‘ Which is FALSE! I don’t even know why I thought that! The water in this situation is not finite; we’ve got a fountain here. We’ve got all the water we need. What does that mean? How does removing that assumption adjust our problem solving strategy?

You’ve probably got it all figured out. Or already knew right off the bat. You’re so smart! *hug* Me? It took me a little longer. So, as the picture says (reads), ‘now what?’ Now we do away with my assumption. Is that 3 gallons of water going to get us anywhere? Do we have any indication that this current setup can find us a single gallon of water to make that 3 gallons become 4 total? No. But we do have 2 gallons there, which is half of 4. And if we’ve figured out how to get half of 4, we just need to do that twice! Where’s that extra container?! Nothing? Dag. (I had to go all the way down to the third separate entry to find the definition that fits the way I use it!) So, what do I do with the 2 gallons?

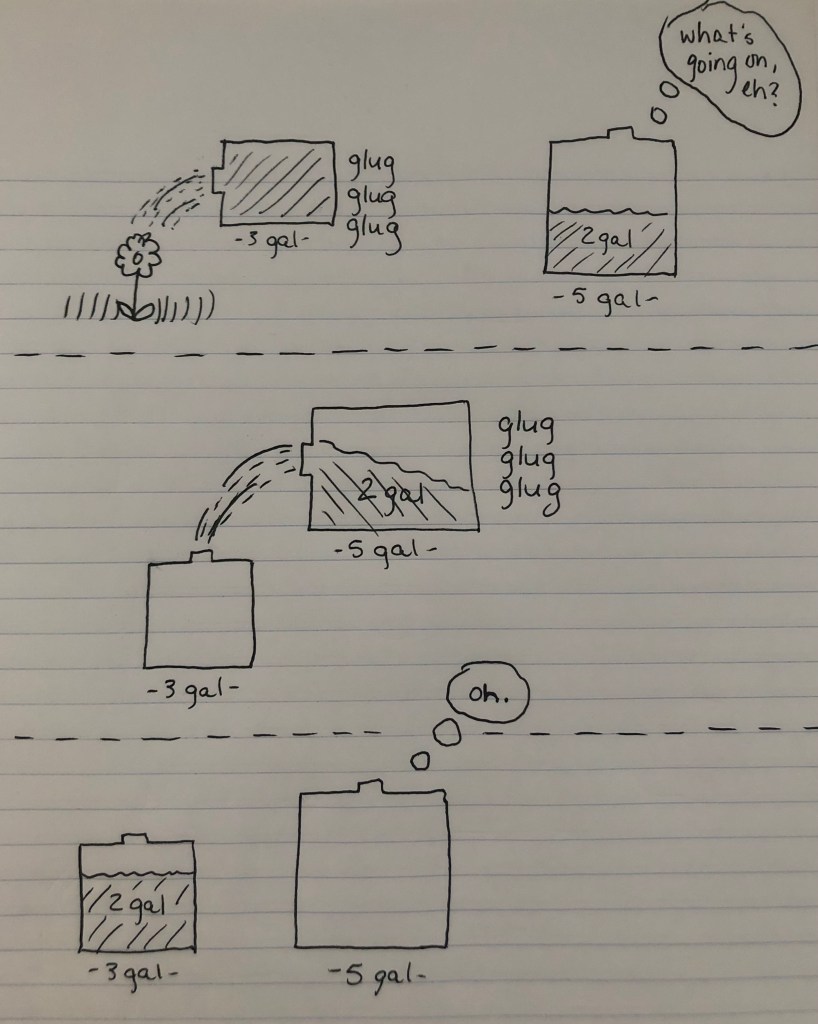

First off, we dump the 3 gallons in the 3-gallon jug back into the fountain (or on a nearby garden or tree or something). Once the 3-gallon jug is empty, we pour the 2 gallons from the 5-gallon jug into the 3-gallon jug, so now it looks like this (or it would, if water jugs (and water) actually looked like they had been drawn by, well, me):

So, now we’ve got 2 gallons of water in a 3-gallon jug, and 0 gallons of water in an anthropomorphized 5-gallon jug. It would be silly to dump the 2 gallons back into the 5-gallon jug, and it would be pointless to fill up the 3-gallon jug, since we already had that and poured it on that nice little flower (bless its heart). So what do we do now? Let’s make use of that vast supply of water we have and fill the 5-gallon jug back up!

Looking at the picture above, we see that we now have 2 gallons in a 3-gallon container, and 5 gallons in a 5-gallon container. Even if we could fit the 2 gallons into the 5-gallon container, that would make a total of 7 gallons of water. Too much. So, what if we try to put the 5 gallons into the 3-gallon container. It wouldn’t all fit. Just… 1 gallon… would, because there’s precisely 1 gallon’s worth of space left in the 3-gallon jug. Which would leave… 3 gallons in the 3-gallon container, and 4 GALLONS IN THE 5-GALLON CONTAINER. GREAT SCOTT!

At multiple points in this riddle, I got lost in the consideration of possible choices and actions. Now, having walked through it with you (and that nice little flower), I feel like my mind has been opened up to possibilities for this. Por ejemplo:

Fill up the 3-gallon jug.

Pour the 3 gallons from the 3-gallon jug into the empty 5-gallon jug.

Fill up the 3-gallon jug again.

Start pouring the 3 gallons in the 3-gallon jug into the 5-gallon jug already holding 3 gallons.

By the time the 5-gallon jug is topped off, you are left with one gallon in the 3-gallon jug.

Empty the 5-gallon jug.

Pour the 1 gallon from the 3-gallon jug into the empty 5-gallon jug.

Refill the 3-gallon jug.

Pour the 3 gallons from the 3-gallon jug into the 5-gallon jug already holding 1 gallon.

There are now 0 gallons in the 3-gallon jug, and 4 gallons in the 5-gallon jug.

Sorry you were deprived of pictures this go-round. I’m afraid if this post gets much longer, something bad will happen. Anyway… Presh offered this alternative solution, as well. So, what have I learned from this?

- Find your preferred method of representation, whether it be numbers, pictures, connect-the-dots, or whatever. It could be purely mental; it could be represented in a partial physical sense (some poorly done drawings, in this case); or go for broke and recreate the entire scenario with jugs and a water fountain (bombs are frowned upon, so leave that part out. just pretend with a kitchen food scale). And make sure you use the water responsibly.

- Watch out for assumptions! Question EVERYTHING. I’m just kidding, that would drive you spare; but do be sure to question aspects of the problem which you initially take as a given. In the above example with the lemonade, it’s easy to assume that both beverages are in a liquid state. That’s not a given, though, as we saw. Maybe try pretending you’re an alien who is new to the planet. Ask about everything: ask about nouns involved (things, like lemonade) and the assumptions we make about them (that drinks are always liquid) or verbs (actions), questioning what’s really happening or what we just assume is happening. Above, the example reads that the drink jugs are emptied. Is that how we normally describe the transfers of liquids? Don’t we typically pour them? What might we empty? And what sorts of contents might something be holding if we empty it? We empty garbage cans, for one thing. Of course, we can empty drinks from one thing into another; it’s not an outlandish turn of phrase. (But don’t empty drinks into garbage cans–that’s a jerk move.) But, anyway, that wording was something I paid close attention to when I was porting over the example from the reading: ‘they didn’t say ‘pour,’ but ’empty,’ which I should have questioned, being the word nerd I am.

So my thoughts on this post were a big more drawn out than last time, but I thought that was a fun exercise to walk through. I know it was good for me, and I sincerely hope you got something out of it, too, even if it was just chuckles and/or an ego boost from my obscenely bad drawings. There is even more to unpack in this first reading assignment, if you can believe it, but I think tackling it in chunks as we’ve been doing makes for better processing of the information. Bite-size pieces, like tiny Snickers bars and that perfect ratio of peanut to caramel to nougat. Om nom.

Thank you for stopping by, and let me know if you have any other riddles or situations like this that you think we should walk through.

-hxrg