Today, we’re going to start by tackling… The Tower of Hanoi. *Cue ominous music and lightning flashes*

Kind of like the Einstein’s Zebra puzzle we talked about way back when, I think this one is pretty common. I believe the first time I encountered it was in listening to an audiobook (don’t ask me which one). It’s a fun little logic puzzle that likely won’t take much time. That hyperlink on the name (above) will take you to a website with a fun little mock-up so you can try your hand at it. If you get stumped, there’s a ‘solve’ button. Click it and it will show you the steps to complete it.

Why are we talking about the Tower of Hanoi? Why, because it was referenced in our readings, of course! It’s been a hot minute since we’ve delved into this MOOC, so I’ll try to bring us back up to speed on it.

MOOC: Methods for Solving Problems, on Coursera

Reading Assignment: “Recognizing, Defining, and Representing Problems” by Pretz, Naples, and Sternberg

Notes:

Here is the description of the Tower of Hanoi problem, in case you aren’t familiar:

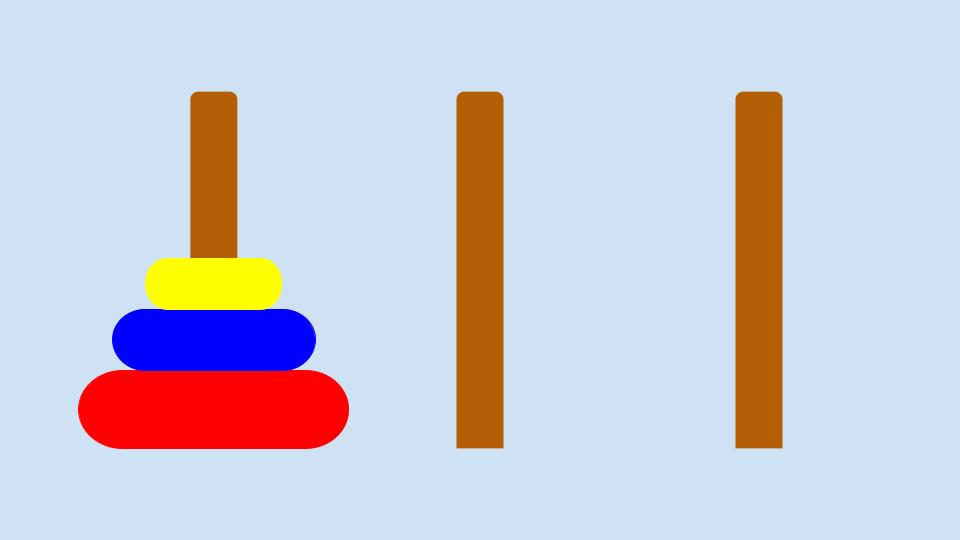

“There are three discs of unequal sizes, positioned on the leftmost of three pegs, such that the largest disc is at the bottom, the middle-sized disc is in the middle, and the smallest disc is on the top. Your task is to transfer all three discs to the rightmost peg, using the middle peg as a stationing area, as needed. You may move only one disc at a time, and you may never move a larger disc on top of a smaller disc.” (Sternberg, 1999)

I made you a picture (it isn’t interactive; I’m not that good yet):

The authors describe the Tower of Hanoi as a well-defined problem.

- Easy to recognize: you must move the discs onto the third post

- Clearly defined: the different posts and the different discs are easy to tell apart, spatially and size-wise–not ambiguous

- Solution path: straightforward, given the parameters and data

So, what do you do? (I feel like Dennis Hopper in Speed… ‘WHAT DO YOU DO?!‘)

You solve it. (Remember: if you get stumped, the link up above will take you to a site that can show you how to solve it.)

As we said, this is an example of a well-defined problem. The thing about it is that some well-defined problems still have to be found. Actually solving the problem may be easy; learning about its existence might not. This circles back to that ‘what do we know, what do we not know’ dilemma.

The authors then follow up with another puzzle, and this one was a real humdinger for me, I must say. I tried my hand at it yesterday with no luck, then again this morning. Finally, it clicked; however, I feel the need to scour my process, because I had so many false starts that it makes me doubt my success. I’d like you to give it a try and let me know how it goes.

“Three five-handed extraterrestrial monsters were holding three crystal globes. Because of the quantum-mechanical peculiarities of their neighborhood, both monsters and globes come in exactly three sizes, with no others permitted: small, medium, and large. The small monster was holding the large globe; the medium-sized monster was holding the small globe; and the large monster was holding the medium-sized globe. Since this situation offended their keenly developed sense of symmetry, they proceeded to transfer globes from one monster to another so that each monster would have a globe proportionate to its own size. Monster etiquette complicated the solution of the problem since it requires that: 1. only one globe may be transferred at a time; 2. if a monster is holding two globes, only the larger of the two may be transferred; and, 3. a globe may not be transferred to a monster who is holding a larger globe. By what sequence of transfers could the monsters have solved this problem?“

Run through it, paying attention to your approach and mindset as you do it. I noticed that once I adjusted how I was looking at it, I had more success.

Good luck!

-hxrg